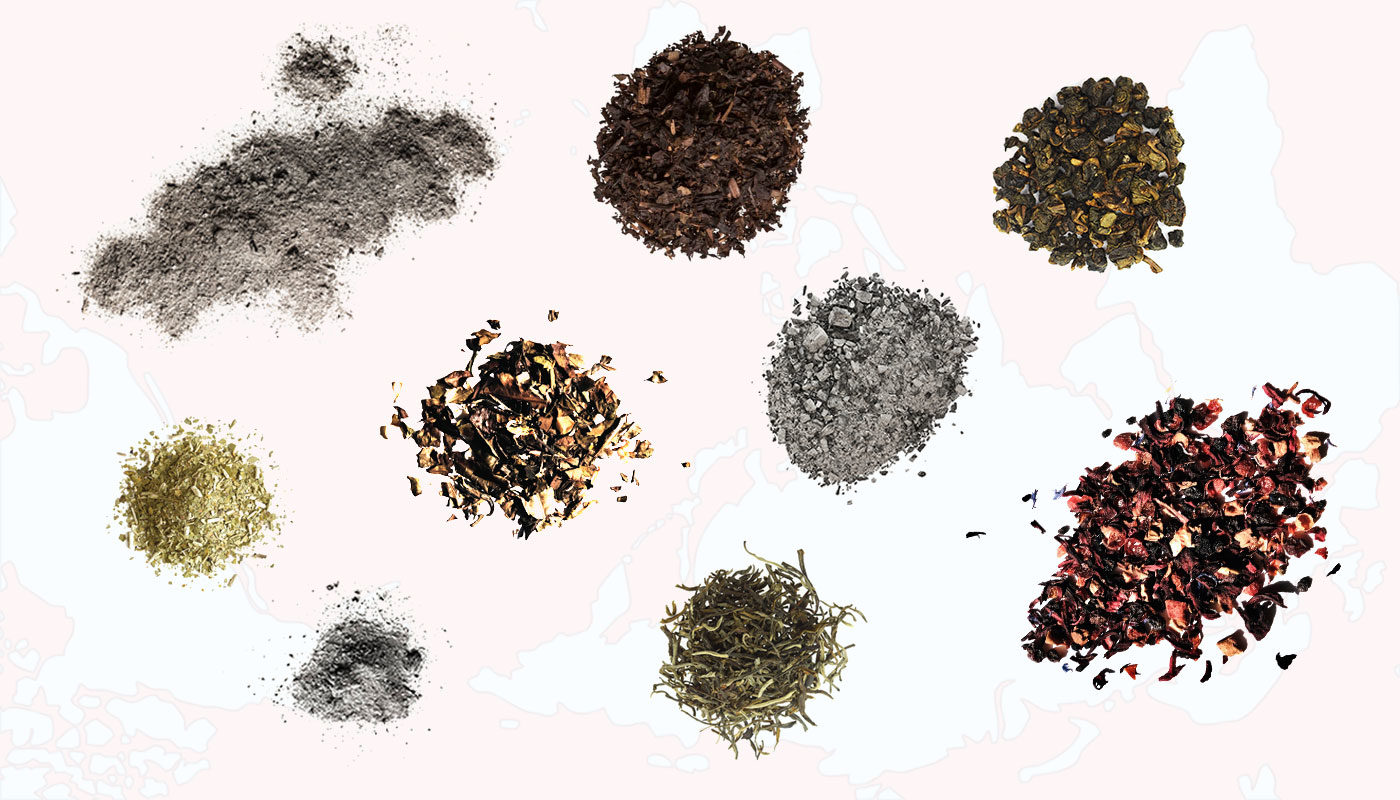

Mate, oolong, jasmine . . . in this personal tale of transnational existence, author Ruru Hoong discovers tea as a throughline across continents and generations, life and death. Following the story, Hoong herself shares her thoughts on bilingual writing, and finally Jack Calder offers a thoughtful interpretation. So put on your kettle, wherever you are, and enjoy.

The Story

一. Mate

“华侨在思想上是无家可归的,头脑简单的人活在一个并不简单的世界里,没有背景,没有传统,所以也没有跳舞。”《谈跳舞》, 张爱玲

I am not typically a superstitious person. But when the cebador pours boiling water into the cup of tea, scalding the ground leaves to a pungent, bitter hiss, I flinch, biting back a reproach. He does not notice my distress; instead, he takes a long swig through the bombilla before handing me the cup.

Gracias, I say, but I don’t mean it. The Spanish feels foreign and tart on my tongue. It is neither auspicious nor professional to oversteep the tea, but what gives me the right to be an arbiter of Argentinian tradition?

Reluctant but not wanting to cause a scene, I take a small sip of the mate for show, its acidic astringence shooting straight up my nose.

Het is goed? He winks at me and pats his hands dry on his pants, leaving dark, palm-shaped imprints. The wail of a bandoneon signals the start of the next tanda. The room is abuzz with tension, cabaceos being thrown across the room, eyebrows raised, looking to harpoon a partner; figures making their way clockwise around the wooden hall.

I arch my neck in his direction, willing him to respond with a nod of his head. He does not. Instead, he finds himself a partner across the room, and crosses it in great strides.

Great, I mutter to myself, the bitterness of the scalded tea still lingering on my tongue. Another tanda to be sat out.

I am so resigned to this fact that I do not see the middle-aged man sidling up to me.

“这么漂亮的女孩,怎么没伙伴儿?” His precise lilt, though accented and tainted by his rancid breath, impresses me. Then disgust fills me for being so easily won over.

“I don’t speak Chinese,” I say, even though I do.

“America?”

“Singapore.”

“Dance?”

There is no etiquette to this one-word exchange; it is a ping-pong match wrought on a dance floor. There is no way to decline a verbal ask, so I accept defeat and set down my long-forgone tea, offering him an extended hand.

I am furious with myself the whole time I am being lifted and manhandled across the floor. This is not dancing. But what can I expect from an inauspicious night, flagrant in its ignorance of etiquette and tradition? He whips my leg up into a boleo, almost hurling my heels into another couple, and I feel myself go rigid in response. He grips me tighter. As a deep-rooted uneasiness churns my stomach, I fight to keep its contents from spilling over his pudgy fingers.

I manage to keep it all in for the duration of the tanda, but it is not a good night. I am hollowed out, empty except for my twisting stomach.

So I am not altogether surprised when I emerge from the dance hall to four missed calls from my mother, and a foreboding message telling me to come home.

回家吧,

公公去世了

二.乌龙 // Oolong

They say that Oolong tea can reduce the risk of heart disease, so the summer before I leave for college I endeavour to sit next to Gong-gong at every meal, refilling his cup far more often than necessary under the guise of filial piety.

But it is no use: with every pour of the steaming tea, he ladles himself another bowl of his favourite laksa. I can see the coconut milk coagulating into fat in those narrowed arteries, white viscous blobs clinging to their walls. No amount of hot tea can wash it down. He turns his shy, cataract-clouded eyes on me and wears a sheepish I’m ever so sorry but I can’t help it smile. All I can do is block his laksa-filled bowl from my parents’ vision before they can snatch it away.

I realise that makes me complicit in his slow march towards death, but all I want is for him to be able to enjoy his remaining days. With the greedy, sheepish delight of a small child, he serves me tea in return, his blue-veined hands trembling with the effort.

Dinners are taken in silence. Though Gong-gong and I have a common language, we have no common conversation. Tea is the only currency of our communication. I pour him another warm cup, watching as his fingers tap the stained tablecloth in thanks:

我

爱

你

The tea evaporates into the chilly air-conditioned air.

It takes 28 hours for me to traverse a quarter the number of time zones, from Amsterdam to London to Singapore to Kuala Lumpur. By the time the wheels of the plane grate upon Malaysian tarmac, the atmospheric chill has settled in my bones, and the warmth has left my grandfather’s body.

三.茉莉香片 // Jasmine

At his funeral, the tea is cold. Sickly sweet. The cloying scent of jasmine makes me swimmy in the head, lightheaded with exhaustion. I feel the tiredness in my eyes, and know they must be red-rimmed. I want to cry, but tears do not come.

“Eat first,” my mum instructs, “Pay respects later.”

I pick up a greasy popiah with my chopsticks, its once-crispy exterior soaked through with oil, and bite down on it. The soggy radish, all at once savoury and flowery-fragrant from the remnants of the tea, settles uncomfortably at the bottom of my stomach.

“Wah, the eldest grandchild is back from Europe!” I hear a booming voice from the back of the room. Is it my second auntie, or my third? I’m not sure. I sit down and take another bite of the popiah, willing it to stay down in my stomach.

Gong-gong was the one who taught me how to hold my chopsticks properly.

He would sit me down at the table with a slender pair of metal chopsticks and hand me a bag of sunflower seeds, instructing me to pick each elusive kernel out and place it into the center of his palm. If any disobedient seed bounced its way to the floor, he bent down to pick it up without reproach or impatience. Cracking open each one on his blackened teeth, he would hand me a fully formed seed as reward.

He always gave me more than he gave himself.

Chopsticks are surprisingly versatile; they are still my cutlery of choice even after years abroad in countries that favour the sharp prongs of a fork and the rounded recesses of a spoon. They can kiap chunks of meat between its two appendages, guide noodles through thin slits, spear fishballs with ease.

But standing in front of the tray of his cindered remains I feel nervous. This is his 股骨, the young funeral director announces to the room. His femur. Not knowing the phrase for femur, I hear 骨骨 instead. Bone-bone.

No shit, I think to myself, he is all bones and no skin.

When it reaches my turn, I am handed the chopsticks and all at once the room feels quite swollen with expectation. You want this instead? The funeral director asks in English, misinterpreting my hesitation. He holds out a pair of tongs with a face full of cheery sympathy. Sorry, this one cannot use fork to pick up, ah!

He earns a few laughs at my expense.

I thought you weren’t supposed to laugh at funerals.

Blushing, I grip the chopsticks tighter, its metal edges leaving dark imprints in my skin. But how can I tell him that my teeth are clattering bone-on-bone, that my fingers are stiff not from lack of practise but from fear, fear that those sticks would cross the wrong way and disappoint Gong-gong, fear that my hands would falter and let his bones slide, let them smash into smithereens on the floor?

For his aged bones are not like the hardy youth of a sunflower seed.

And Gong-gong is no longer here to pick them up.

The humid air gags my throat as I pick up the largest bone from the mass of gritty pink residue. My chopsticks hover gingerly in the air, threatening, quivering.

I drop the bone into the urn without incident.

But something about the way it chips and disintegrates against the plastic walls makes the bile rise up from within me; I first feel a vague dampness in my oesophagus and tear away just when the walls of my stomach squelch and contract—I mutter my apologies as I make my bumpy escape to the bathroom:

I am delighted,

delighted as I unload the contents of my stomach into the gilded sink,

delighted that I can feel again with such intensity,

delighted by the relief that settles in the tips of my fingers.

四.白牡丹 // White Peony

The heady incense emits a white smoke, but my head remains clear for the duration of the drive from the crematorium to the columbarium. My dad carries the burning joss sticks for the entire drive, releasing frightening, guttural cries out his open window:

爸,跟着我们

爸,跟着我们!

I don’t believe in ancestral spirits, none of us do, but we follow the tradition anyways. In the clarity of my rejuvenated state of mind, I find it antiquated and awkward. But I mutter it a few times under my breath.

公公,跟着我, please?

We have tea, after, in the opulent lobby of the columbarium. I hold up the teacup, its bone china strangely cool against my lips. The tea is pure and light, a fine spring harvest from the mountains of Fujian. It is a homecoming for Gong-gong, for it is from Fujian that my great-grandfather began his journey to the Malaysian border, beginning our long collective sojourn across the globe, in search for a better life.

My flight back to London boards in the next hour, so I get up hurriedly to leave, bidding my rushed goodbyes and promises to return soon, which are made to be broken. I have gone as quickly as I have come. As my aspirations circle me further and further away from home, I am no longer sure what I am searching for, or what it is I am trying to prove.

My father has a theory for this: offering up a laugh aching of resignation, he tells me I am looking to emulate the nomadic nature of my Hakka ancestry.

It is in our blood, he says, in our bones. 在骨子底里。

I return to this moment every day as I steep my morning brew. I sit down, breathe in its light floral aroma. And offer my Gong-gong a cup of tea.

Brief Interview

Deva Eveland: Can you talk about your decision to write in both English and Chinese?

Ruru Hoong: I’ve thought about this a lot, because translating it into one language would make it more accessible to wider audiences. But I think a lot of meaning is lost in translation, and my strong sense of attachment to the title of the piece — 骨瓷 — was what made me keep parts of it in Chinese. Bone-china doesn’t sound particularly significant in English, but 骨瓷 conjures up many more associations and vivid images for me, perhaps because of how Chinese in its written form is such a pictorial language: (i) firstly, 骨 means bone, and the imagery of bones is very central to this piece. What drove me to write this piece was the striking moment when I was expected to pick up my grandfather’s ashes and place them in an urn: that scene is still etched into my memory, 刻骨铭心. Feeling the brittleness of my grandfather’s bones through my chopsticks was when his death really hit home for me. (ii) 骨瓷 is bone-china, a fine porcelain. Given the importance of tea — and tea as ritual — to this piece, it seemed apt to reference the vessel that holds the tea. But it also has meaning in another sense: (iii) bone-china is called 骨瓷 because it indeed contains exactly that — bone, which makes it one of the strongest types of porcelain there is, which allows thinner, finer cups to be produced. I recently picked up ceramics during lockdown and have been fascinated with porcelain as a material — it is so much more compact than other clays, and allows me to be so much more precise with what I want to make, so I very much liked the idea of titling the piece that: in some ways it is a reflection on how the heaviest of things can simultaneously be the lightest of things. (iv), I think there’s also something very poignant about the fact that you add animal bone — literally, the material of death — to strengthen the vessel in which you drink your daily nourishment out of. My grandfather has, in his small but meaningful ways, made me who I am today. His sacrifices enabled my father to thrive, and it still fills me with a sense of wonder that a young boy from a village in the middle of nowhere Malaysia could’ve made it to where he is today! And (v), lastly, not many people know this but bone-china is actually an English invention (despite the word China in its name… though unsurprisingly, China is now the world’s largest producer of bone-china!). The British empire had their hand in everything (including the ex-colonial outpost of Singapore…), so I found that appropriate and mildly ironic. Also, at the time of my grandfather’s death I was living in London, so the relevance of both UK and China to this material made it seem like a very apt title.

As for deciding what to translate, and what not to translate: I try to make the piece accessible even to the non-Chinese speaking reader without taking away the authenticity of the communication, if that makes sense. For example, I translate femur because it was a phrase I didn’t even know myself! I don’t translate others when the meaning is implicit through its context. I’m a strong believer in this: if we can leave French and Spanish phrases untranslated in mainstream English writing and leave it to readers to infer from context, we should be able to do so with Chinese!

Critical Accompaniment

In one of the aphorisms included in his Pensees, Pascal writes this: “there is nothing, just or unjust, which does not change in quality with a change in climate. Three degrees of latitude overthrow jurisprudence. A meridian determines the truth. Law has its periods; Saturn’s entry into the house of the Lion marks the origin of a given crime. It is an odd kind of justice to have a river for its boundary.” Here he is discussing justice, but the thought applies equally well to customs or culture. It raises the question of how we understand what is right, and observes that what is “right” seems to change almost arbitrarily, wherever we go. To burp at the end of a meal in one country indicates respect, in another it is an insult. The situation is absurd but compulsory. Wherever you go, you must act “right,” and everywhere “right” is different.

This is the conflict at the heart of Ruru Hoong’s story Bone China. The narrator laments, in her first words, the clumsy way an Argentine brews mate. Immediately she feels she should reproach the man. Any fool could see he’s burning the tea, which is “neither auspicious nor professional.” But it’s here that Pascal’s paradox rears its ugly head. “What gives me the right to be an arbiter of Argentinian tradition?” What indeed? The narrator knows that the man is wrong, but he is full of the blithe confidence of someone at home, and she, an alien, is compelled by the context whirling around her in dance. She must submit, or at least observe the delicate restraint of a guest. At least here, the man is right.

But the narrator doesn’t simply identify with “her” culture. This is not a tale of the citizen among barbarians, who sees other practices as affirmation of the righteousness of their own. She is alien not only to other cultures, but also her “own.” This is not only because she is cosmopolitan, western-educated, raised in the quintessential “third culture” city of Singapore, etc. No, it’s because Pascal’s paradox cuts both ways. If it is impossible to say the Argentine is wrong, how is it possible to say the Chinese is right?

The figure of Gong-Gong holds the key to this question. I say the figure, and not the man, because the slow differentiation of the two in the head of the narrator constitutes the whole drama of the story. This is because although Gong-Gong is a beloved old man with a taste for laksa, he is also an educator, the man who initiates the narrator into “Chinese-ness.” In the chopsticks scene we see his split role. As beloved Gong-Gong, he spoils the narrator with sunflower seeds, but as educator, the chosen avatar of Chinese culture, he subjects the narrator to cultural discipline. From beloved Gong-Gong there comes no reproach for the narrator’s failures—but that’s because Gong-Gong the educator’s reproach is implicit. You dropped the seed. You failed. You were not right.

Gong-Gong’s split purpose gives an ambiguous twist to the closing line of the scene: “[Gong-Gong] always gave me more than he gave himself.” Certainly, the beloved Gong-Gong is a fountain of seeds, but those gifts only come on the condition that the lesson is learnt. The man who exacts that toll is the figure of Gong-Gong, a superior being who demands submission to the culture as right. It is true that this figure, the educator into culture, can only give—language, rituals, techniques, forms—but its gifts are compulsory. They are not to be tampered with or strewn about willy-nilly. One must take them exactly as they are. It is this demand that the narrator struggles with, the demand of a culture to be right, and the struggle takes the form of the question: “what does Gong-Gong mean to me?”

How can he love me and yet demand my submission? How can he be sure what he teaches is right, when others, no less sure, teach differently? How can I love Gong-Gong and yet think differently from him? The narrator sits, paralyzed, at Gong-Gong’s side. She watches him eat laksa and wonders at her own inability to act against him, or even to communicate. She describes this dilemma: “Though Gong-gong and I have a common language, we have no common conversation. Tea is the only currency of our communication.” As a result of collapsing the figure of Gong-Gong and Gong-Gong the man, the narrator cuts herself off from him. She knows the figure of Gong-Gong brooks no objections, so she cannot object in favor of Gong-Gong the man. The figure of Gong-Gong taught her language, but his superiority means they can never use language together. Instead, language becomes like “currency.” Words appear not as tools by which we communicate with other people, but as fixed and self-determined objects. A coin simply is what it is, and can only be passed mutely from hand to hand. The narrator wishes to talk to beloved Gong-Gong, but in her way stands his figure. The tragedy of this position is revealed in the narrator’s desperate projection onto Gong-Gong. If he cannot say it, at least the tap of his fingers do: “我爱你.” She must imagine there is love, goodness in this regime, but even as she grasps at it, “the tea evaporates into the chilly air-conditioned air.” The currency of her words is revealed to be the empty passing of coins, and she is left with nothing, only a growing nausea.

It is only at Gong-Gong’s funeral ceremony that this nausea finally finds expression. Although the narrator performs the ritual of the bones perfectly, “something about the way [Gong-gong’s bone] chips and disintegrates against the plastic walls makes the bile rise up from within me.” As she said before, “Gong-gong is no longer here to pick himself up.” Gong-Gong the man can no longer supply a loving face for the discipline of culture. And so all her discontent with that culture—her struggle with its absurdity in the face of the Pascal paradox—suddenly surges up. She vomits, and that vomiting frees her from Gong-Gong the figure, and delivers her, finally, Gong-Gong the man, whom she loves.

This is “homecoming for Gong-gong,” his real homecoming, from an irreproachable figure of culture into the man himself. And just as the narrator overcomes the split in Gong-Gong, she overcomes it in herself. In letting go of the figure of Gong-Gong, she frees herself to criticize culture and tradition, and finds it can’t hurt her beloved Gong-Gong a bit. She can deny and love at once. Untied, circling “further and further away from home,” the narrator has loosed herself into an alien world, but one in which she is now capable of acting. She realizes that words are not destinies, not coins, and that promises “are made to be broken.” In other words, that her promises are her own, her actions her own—and that whether they are “right” is not a settled question.

The narrator admits it: “I am no longer sure what I am searching for.” But it is only because she accepts this—the ambiguity of her desires and actions—that she can finally offer tea to her Gong-Gong, as it is only now that she can brew it herself.

—Jack Calder

Ruru Hoong was born in Singapore and has lived in Shanghai, Singapore, the Bay Area, and London. Her writing is very much influenced by the clashes and confluences of the cultures that she lives and has lived in. She is a 2020 graduate of Faber Academy in London and is currently editing her first novel.

Cover art by David Huntington

Interview conducted and edited by Deva Eveland

Critical Accompaniment by Jack Calder