Translated by Jesse Young and Xiao Yue Shan

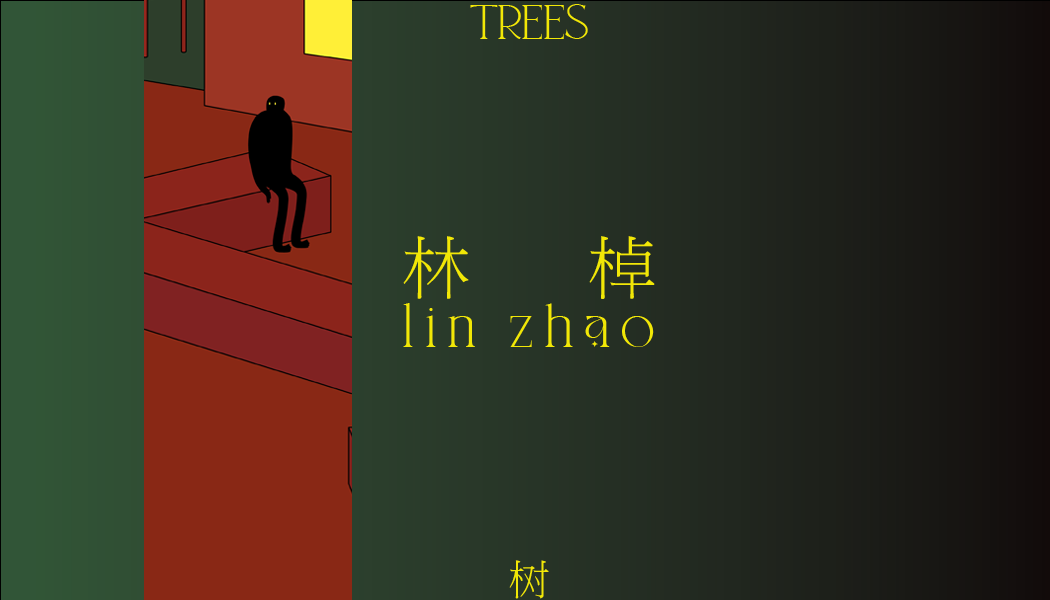

Lin Zhao’s incredibly powerful, singular, and award-winning novel Liu xi was published in 2019, and immediately announced her as a voice to watch in contemporary Chinese letters. In this brief excerpt from the chapter “Trees”, the reader gets a sense of her winding, Nabokovian style, which at once rejoices in the ornate capacities of language without sacrificing its symbolist potentials. Translated by Jesse Young and Xiao Yue Shan, the narrative prose deftly embodies the luminescence of poetry.

To read more from Lin Zhao, check out Spittoon Literary Magazine Issue 7, available in March.

树

我向杨白马描述过一些童年早晨——倘若白兰树影指向西方,你就能在树下遇见它们——我正好行过梦和真的边界,暴露在梦潮之外的身体冷却为干峥峥礁石。这串悬浮的时空教会我灵魂印花的秘术。 动作要轻。发力是大忌。花纹来自床单——莲座式花冠、带齿匙瓣、回旋枝条是牡丹和藤本植物的离奇杂交,只在床单厂商浮夸的头脑里成立——那时的我尚不了解自然之原理造物之逻辑,反倒感激有人虚构那充满分岔、弯道和流线的宇宙供我沉溺, 我的底纹因而是充满冗余的、自我满足的、虚张声势的——花与枝不断微调舞步,直到与梦的浪涌合 拍,直到浪涌将花纹推向我轻轻晃动的灵魂,留下一层比晒痕更浅的印迹。许多年后我误入虫洞, 听一个年轻放荡的女人反复弹奏《烦恼》,到第八百四十遍时,那些枝条的幽灵突然重临我身。

我的意思是,当我们静下心来,放下成见,仔细对最初的光阴(我刚从彼方脱身)筛汰一番(用一只 捞网),定会发现网眼上挂满闪闪发光的晶体。你举着那样一只闪闪发光的捞网,我也举着那样一只 闪闪发光的捞网,在最初时刻,我和你并没有什么 不同。我们因清白而安宁。你坐下来安静地拆你的回忆,直到那个离你最远、只剩一抹灰影的部件被你一捏住就倏然飘散,安宁便是你抓得住的仅存的 东西:它是你穿越过的、牢牢记住的门,是你最终想回到的门。项迪是门的其中之一扇。当我在他的宫殿深处轻拍殿柱、步向终点(我预感到那个终点), 就像以往和以后的任何一次,我知道安宁已然降临, 我愿意让毕生岁月都在那一刻、那一处用尽……而实际情况却是,真爱引发的癔症抽打我,将我从他 眼底扔出去、跌回狂欢的人潮当中——看,千禧年彩带飘下来了。

Trees

I described some of my childhood mornings to Yang Baima—if the shadows of the white sandalwood point westward, you’ll be able to meet them under the tree—and I just happened to be passing the liminal zone between dream and reality, my body left out of the sea of dreams, sustained like a reef stilled in water. This suspension of time and space taught me the secret magic of soul imprinting. Movements must be light. Force is a great transgression. The pattern of one’s own bedsheets—a crown of petals like holy lotus, toothed-spoon petals, its orbiting branches a result of the curious hybrid between peony and vine, a species only existing in the imaginations of bedsheet manufacturers. At that time, I did not yet comprehend the logic of nature and creation, but I was deeply grateful that someone had conjured up that divaricating, serpentine, sleek universe into which I could deeply sink. My blueprint was full of excess, selfishness, and pretense—but the flowers and branches kept adjusting their choreography, until they were in sync with the dream-tide, until their surging patterns pushed in upon my wavering soul, leaving an impression even shallower than sunburn. Years later, I fell into a wormhole, listening to a young, salacious woman perform Troubles on repeat. Upon the eight hundred and fortieth rendition, the phantoms of those branches suddenly reappeared to me.

What I mean is, when we quiet ourselves, lay down our presuppositions, and carefully sift (with a net) through those first times (having freed myself from the other side), we’ll find luminescent crystals hanging in the eyes of the mesh. You’re lifting up the net throwing sparks, I’m also lifting up the net throwing sparks. In that initial moment, we’re the same. We’re innocent, at ease. You sit, peacefully pulling open your memories, until that most distant piece—almost completely free of shadow—wafts away just as you pinch at it. Tranquility is the last remaining thing you can keep: it is the door you’ve gone through, the door you firmly remember, the door to which you ultimately wish to return. Xiang Di is one of the doors. When I was in the inner depths of his palace, lightly tapping the pillars, stepping towards the end (an end I foresaw), it was as if, in all the moments that came before and would come after, I would know that tranquility had descended. I want to corral a lifetime into that moment. To exhaust that place to its end… But the truth of it was that the hysteria of true love lashed into me, and I was tossed from the depths of his eyes, tumbling back into the euphoric crowd—look, the millennium’s confetti is floating down.

林棹,1984年5月生于广东深圳。中文系毕业。从事过实境游戏设计,卖过花,种过树。《流溪》是她的第一部长篇小说,首发于《收获》2019长篇专号(夏卷)。2020年,凭借本书,林棹入围第三届宝珀理想国文学奖决选名单。

Lin Zhao, born in May 1984 in Shenzhen, Guangzhou. Graduated from the department of Chinese Language. Has worked in game design, has sold flowers, has planted trees. Liu Xi is her first full-length novel, first published in the 2019 summer volume of Shouhuo. In 2020, with this publication, she was shortlisted for the third Baopo Lixiang National Literature Award.

Mostly Jesse Young 杨哲思 messes around in the playgrounds of poetry and stop-motion—eyeballs, hands, Japan and insects recur frequently. On occasion he might translate the errant poem or story—he does these things for himself but doesn’t mind sharing. Though he holds degrees so broad as meaningless and treats hobbies like fast fashion— some say he is redeemed by quixotic commitments (in love and art). His YouTube series on Chinese science fiction is called HSFK and he is working on a podcast about Chinese film. He believes this is his first published translation.

Xiao Yue Shan is a poet and editor born in Dongying, China and living in Tokyo, Japan. shellyshan.com.